Full renovation of West school possible by 2023 in D-11 property-tax request

School District 11 Superintendent Nick Gledich answers a question during a presentation to the Garden of the Gods Rotary. Westside Pioneer photo

|

But voters weren't convinced, and both measures failed.

So officials in the area's largest school district (which includes the Westside) went back to the drawing board. A single measure, this time for an MLO only, will be on the ballot in November. A permanent property tax hike, it is estimated to bring in $42 million a year.

It would hit the wallet more lightly than the 2016 plan, pay off most of the district's existing bond debt by 2023 and achieve almost the same results as last year's two-measure proposal, except over a longer period of time.

“The big win is that the taxpayer is paying so little in property taxes for this plan,” said Glenn Gustafson, D-11's chief financial officer, in a recent interview. “It's a little bit complicated because we're paying off the debt, but that's the beautiful part. The important thing is being patient enough to get there.”

Because of the debt payoff, district estimates show the highest tax bills occurring at first. For example, the owner of a home valued at $250,000 would pay $18 a month in 2018, which is higher than the first year in last year's proposal.

But instead of an upward trajectory after that (as in last year's plan), the rate would go down. By 2024 - the last year for which the district provides an MLO estimate - the monthly hit for that same house is projected to be $6.26.

Meanwhile, with the debt reduction (and corresponding interest savings), more of the MLO revenues would become available each year, explained Gustafson, who himself is a graduate of the district's Doherty High School (Class of '78).

The target of those proceeds are identified in the MLO as bolstering school security; enhancing technology; adding guidance counselors, psychologists and nurses; reducing class sizes; increasing teacher pay; beefing up charter school funding; and upgrading infrastructure.

Regarding the latter point, the MLO ballot item does not include a promised list of building-improvement projects (as a bond issue would).

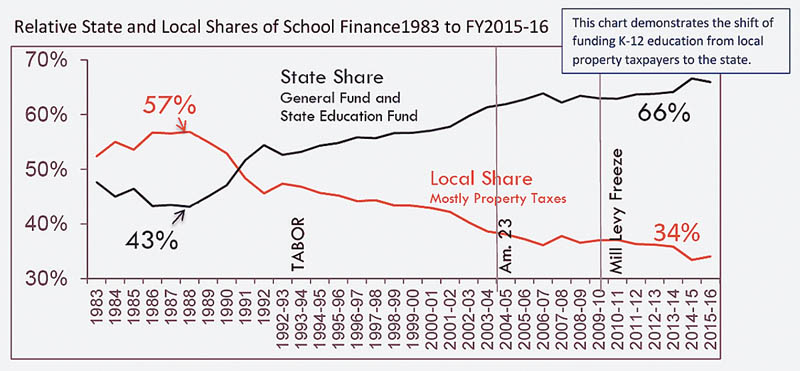

This is a graphic provided by District 11, showing how changes in state laws and policies have led Colorado school districts to obtain steadily lower percentages of their funding from local property taxes. A recent offshoot of that is districts, including D-11, seeking mill levy overrides from their constituencies. Courtesy of School District 11

|

The district's MLO web page (d11.org/mlo) does show about $4 million worth of current, less pricey needs at various schools, including those on the Westside.

However, once the debt is paid off in 2023, the plan is to use $17.55 million of the $42 million each year toward major work. This could mean complete renovations of several older schools, Gustafson said.

In each case, a long look would be given to the concept of leaving the historic exterior while gutting the interior and installing state of the art utilities and technology.

One school on that informal list is the original West Junior High, built of brick with some ornamental design, which will be 100 years old in 2024. Now dubbed the “West Campus,” it contains West Middle and West Elementary schools.

In a recent interview, Gustafson was joined by Superintendent Nick Gledich in pledging to work closely with the local community on how the West renovation would be done.

Last year, when the bond-issue ballot item left open the option of tearing down the old building, the Old Colorado City Historical Society pleaded with D-11 to abandon such a scheme.

Why just an MLO this time? Because the vote was closer on the MLO than on the bond issue in 2016, it would seem to have a better chance of passing this time, Gledich believes. And surveys have indicated that voters aren't necessarily bothered by the idea of a “forever tax,” as it's been called.

An MLO is also more flexible, from a building standpoint, than a bond issue with specifically required expenditures. Changes can be made based on changing needs or emergencies (such as a major water-line break at West two years ago), Gustafson noted.

One issue in building support for the plan within District 11 is that well over half of those expected to vote are over 55 years old - which generally defines people who no longer have kids in school or never did. An argument to such people is that improved schools can help raise property values, the finance officer said.

D-11 is set up for accountability should the MLO pass. A citizen oversight committee is to “monitor all MLO funds for accounting accuracy and program benefit,” the district website states.

In addition, a separate accounting fund will be used “in order to properly track all expenditures,” the website continues. This makes D-11 “the only large school district in Colorado that places 100 percent of its mill levy override funds into a separate accounting fund in order to properly track all [its] expenditures.”

Why go to the district for more money? The need stems from a complex tangle of state financial issues and regulations, intensified by Medicaid which is “the fastest growing part of the budget,” Gustafson said.

As the graphic on this page shows, less and less school money statewide in recent years has been available from local property taxes - dropping from about two-thirds of district budgets in the past to one-third now.

But at the same time, state legislators have not been able to deliver the amount of funding the school districts believe they deserve - despite Amendment 23 (passed by the Colorado Legislature several years ago to bolster education) and tax revenues from legalized marijuana.

“The state basically told us, 'We don't know how to solve this problem.' They told us to go to our own districts,” Gustafson said.

The catch is that some school districts have a better chance of being successful than others in that regard. “The rich [districts] are going to get richer and the poor are going to get poorer,” Gustafson summed up.

District 11 now spends $2,685 less per pupil than the national average (as of 2013-14), the district website states, and is “continually losing ground in our ability to compete,” Gustafson asserted.

Lower salaries in D-11 have made it harder for the district to retain or hire teachers and support staff. Even kitchen staff positions have gone unfilled, and in some occasions there haven't been enough bus drivers to run all the routes, he and Gledich revealed.

These and other kinds of problems related to funding contribute to D-11 losing students. The hope, Gustafson outlined, is that passage of the MLO can reverse this spiral.

Westside Pioneer article